Thérèse of St. Augustine and Companions

By Leopold Glueckert, O. Carm.

During the most violent phase of the French Revolution, the so-called Reign of Terror, an estimated 40,000 people lost their lives at the guillotine. A disproportionate number of those were religious sisters and brothers, priests, bishops, and dedicated lay Christians. This sad episode took place because a small but dedicated core of anti-clerical leaders attempted to remove religious and church influence from French society.

The Carmelite sisters in the quiet town of Compiègne had no wish to meddle in politics, but only to offer intercessory prayer for those who asked for help. But in the autumn of 1789, the National Assembly began a series of dramatic measures to address the national debt. Within just a few months, all Church property was nationalized, and declared available for sale. Then all religious vows were declared null and void, based on the assumption that most men and women religious were held prisoner by evil superiors against their will. According to the plan, the “liberated†religious would then gratefully leave their houses to enter the work force.

The Carmelite nuns of Compiègne were a typical, good community in many ways. There were 20 of them in 1789, with 50 years between the ages of the oldest and youngest, and representing every social class in French society. Their epic story has been immortalized in the screen-play Dialogues of the Carmelites by Georges Bernanos, and by Francis Poulenc’s powerful opera of the same name. Their prioress was Thérèse of St. Augustine, elected at the age of 35. Like her namesake a century later, Thérèse had a deep sense of trust in God’s goodness.

Following the abolition of religious orders in 1790, a government official visited the convent in August, and was surprised that each member of the community refused the “ridiculous freedom†which he offered. In fact, the nuns’ courage was blessed with sufficient time to prepare for the worst. They were not required to actually leave their house until September 14, 1792. The date seemed symbolic, since it is the Feast of the Holy Cross, when Carmelites begin their long period of fasting to prepare for Easter, celebrating the Resurrection of the Lord.

Mother Thérèse and the community had decided to take advantage of the two previous years in order to prepare themselves for their ordeal. Although they were very ordinary women in many ways, they seemed to grow in strength as their tribulation mounted, and they appealed to God for help. They made a conscious commitment to offer themselves as victims, if God wished such a sacrifice, as they prayed for peace between France and their Church. They resolved to follow the Lamb of God, Jesus crucified and resurrected. According to their previous plans, they now split into groups of 4, adopted secular dress, and lived in separate houses, where they continued their simple and prayerful life. Mother Thérèse urged them to renew their dedication every day for the next 2 years.

As the Reign of Terror drew toward its bloodthirsty climax, 16 of the sisters were denounced and arrested for living the religious life in violation of the constitution, and supporting the royalists. After a 2-day trip to Paris, they were presented to the revolutionary tribunal and accused of being religious fanatics and supporters of the King. The outcome was not much of a surprise, and all of the nuns were condemned to die on July 17th. Mother Thérèse took advantage of their final days to offer one final service to her sisters. Based on the remote preparation of almost 4 years of prayer and sacrifice, they all renewed their desire to give their lives for the reconciliation between church and state. Their final night of prayer served as a brief “retreat†leading to their final steadfastness.

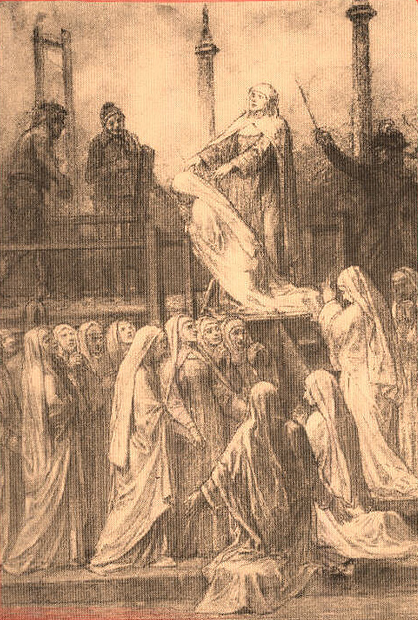

Imagine the shock of the jaded population of Paris when they saw Carmelite nuns, riding joyfully to their death at the scaffold, and singing the Miserere, Salve Regina, and Te Deum.  When they arrived at the guillotine, they intoned the Veni Creator Spiritus. Thérèse of St. Augustine asked to be the last to die, so that she could encourage her sisters. Contemporary accounts tell of the remarkable silence of so many people in the square, as the heavy blade fell and rose again, time after time. It was becoming increasingly obvious to the bloodthirsty mob that these gentle women were not a threat to public safety, and that the violence against them was pointless. By the end of that same month, the Terror had ended.